Hi everyone,

My name is Melissa Strong, and I will be your visualization guide this week.

In the first article, I talked about how I think about tools as part of a broader visualization process rather than as isolated solutions. That idea carries directly into this piece. Before we even write code or finalize charts, we make decisions about structure, hierarchy, and emphasis. Those decisions shape how data is understood long before it is rendered on a screen.

In this second article, I focus on Penpot and where it fits into that early design and prototyping stage. Not as a replacement for every design tool, and not as a declaration of what anyone should be using, but as an example of how open source tools can support visualization work in a practical way.

We will look at why prototyping matters, how design affects function as part of the visualization lifecycle, and why openness in design deserves the same attention we already give to open data and open code. As always, the goal is not to crown a winner, but to understand trade-offs and choose tools intentionally.

If the first article was about the visualization toolbox as a whole, this one zooms in on a single step in the process and asks what it means to design openly.

Why Design Comes Before Charts

When I have an idea for a data story or visualization, I have to fight back the urge to immediately start designing in Illustrator or coding HTML and CSS. Those tools are familiar, and jumping straight into them feels productive.

But familiarity is not the same as clarity. Starting with a sketch makes it easier to surface problems early; before committing to pixels or code. It is far easier to abandon a rough concept than to scrap a polished chart that never quite worked.

My sketches are not pretty. They are not meant to be. They exist to get ideas out of my head and onto something tangible. The limitation is that they are rarely legible enough to share, which is where digital prototyping becomes useful.

Prototyping as Thinking, Not Decoration

Prototyping is often treated as a cosmetic step. For visualization work, it plays a different role.

Many teams rely on tools like Figma for wireframing and mockups. It is capable and widely adopted, but it also comes with constraints. It is cloud-only, and while there is a free tier, meaningful collaboration requires a subscription.

This is where Penpot becomes interesting.

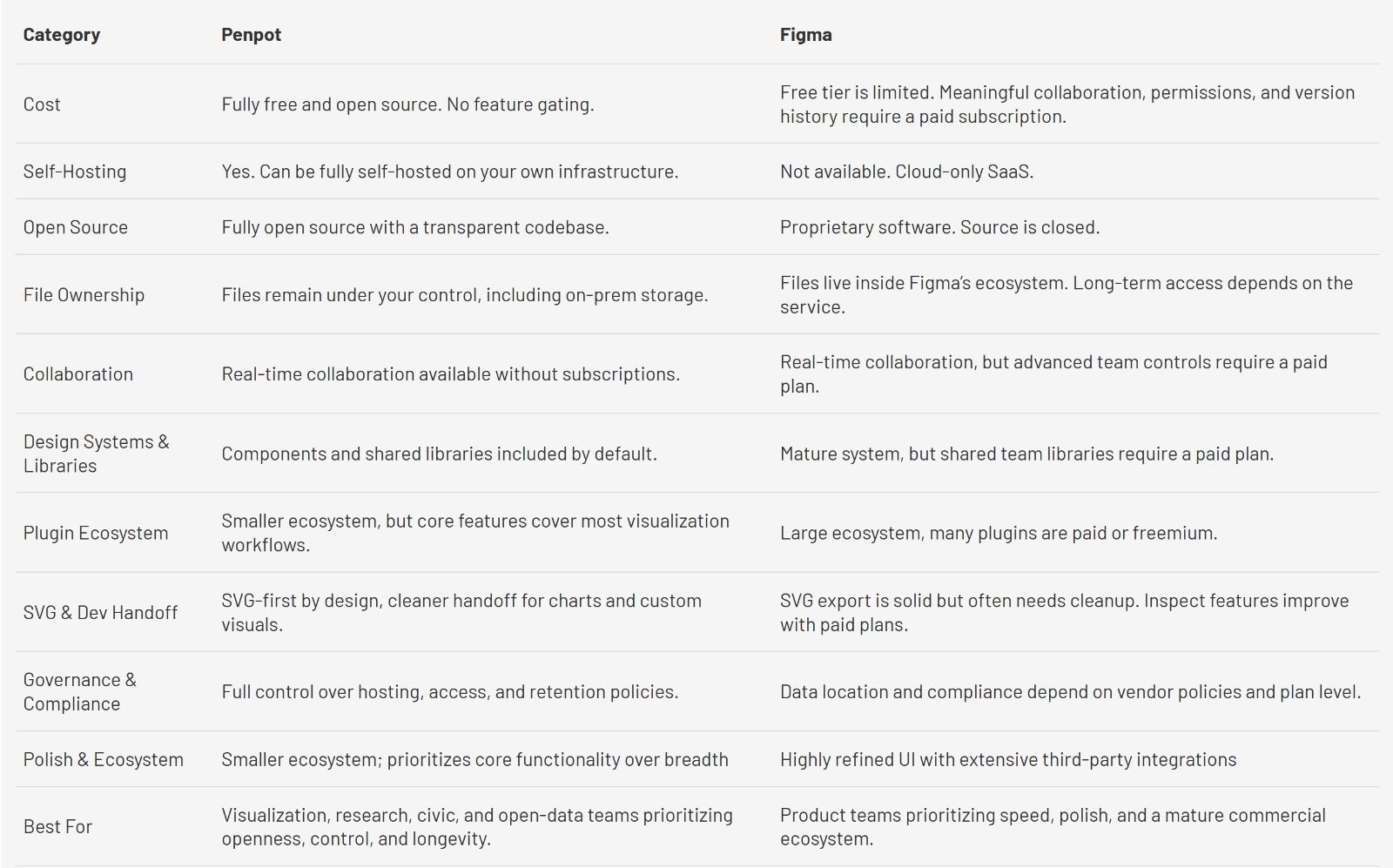

Rather than walking through feature-by-feature comparisons, the table below highlights the differences that matter for visualization and data-driven work. This is not about which tool is better, but about which constraints matter for different kinds of projects.

Many visualization teams already use Figma, and for good reasons. Penpot is not a replacement for every workflow. It is an alternative that aligns better with open and long-lived visualization projects.

Categorical features comparison table: Penpot and Figma

From Sketches to Collaboration

Paper sketches are excellent thinking tools. They are fast, flexible, and forgiving, which makes them ideal for early exploration. Their weakness is collaboration. At some point, a sketch has to become legible to someone else. Not polished. Not final. Just clear enough to support a shared conversation. Digital prototyping fills that gap, acting as a bridge between private thinking and collaborative decision-making.

The goal here is not fidelity. It is alignment.

Original sketch (left); Mockup in Penpot (right)

Why Open Design Tools Matter

Visualization projects often have a longer tail than we expect. A chart built for a report gets reused in a presentation. A dashboard evolves into a reference tool. A graphic resurfaces years later in a new context.

Design artifacts are part of that lineage. When those artifacts are locked behind proprietary formats or access models, they become brittle. You may still have the data, but you lose insight into the design decisions that shaped how it was presented.

Open design tools reduce that fragility. This is not about ideology. It is about durability.

Designing Beyond Templates and Treating SVG as a First-Class Output

Many design tools optimize for speed through repetition. Templates and presets are powerful when the work fits predictable patterns. Visualization work often does not.

Even familiar chart types tend to be adapted. Axes are emphasized or suppressed. Annotations carry meaning. Layouts bend to narrative needs. Tools that privilege templates can quietly push designers toward sameness, even when the data calls for something else.

This is where Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) matters. SVG sits at the intersection of design and implementation. When treated as a first-class output, it shortens the distance between design intent and code.

Developers can inspect structure, reuse elements, or rebuild visuals directly using D3, Observable, or custom JavaScript.

In this context, SVG is not just an export format. It is a shared language.

Selecting an object in Penpot will reveal the HTML, CSS, and SVG code used to create exactly what you designed in the interface.

Choosing Tools Based on Values, Not Trends

Tool choices are rarely neutral. They encode assumptions about speed, convenience, control, and ownership. In visualization work, those assumptions influence not just how something is built, but how long it remains accessible and credible.

Open source tools are not inherently superior. They are simply better aligned with certain values. For projects that prioritize transparency, reuse, and long-term access, that alignment matters.

If we care about openness in data, we should extend that care to the tools we use to design how that data is seen.

Designing for Openness is a Choice

Open source in visualization is often discussed in terms of data and code. Design is usually left out of that conversation. In practice, design decisions shape interpretation just as much as numbers do.

Choosing open design tools does not automatically make work better or more ethical. What it does is make the design process more transparent, more durable, and easier to revisit.

Designing openly is not a requirement. It is a commitment.